Ballymoney Town Hall

In 1863, the people of Ballymoney began planning a new civic building. It was to be known as the new Assembly Rooms and would include a library or reading room, chambers for the Town Commissioners, a public function room and a display area for the town’s museum.

To pay for the construction, £1,300 was raised by public subscription, and a substantial amount was collected through a fundraising Bazaar.

The building has provided an invaluable service to this community since it opened in August 1866.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the Assembly Rooms had become known as the Town Hall. By 1932, the Town hall needed urgent restoration and repairs, and work began on £6,000 worth of renovations. The Town Hall was re-opened by the Honourable Mr Justice Megaw on Friday, 16 February 1934.

The Town Hall was now fortunate to have a magnificent stage in the main hall, which the local town guide book later described as “perhaps the best small theatre in the Province”. This became the venue for the still famous Ballymoney Drama Festival, launched within a fortnight of the Town Hall’s official re-opening.

In 2005, the Town Hall was restored, with a new museum and tourist information centre added to the rear of the building. It continues to be an essential amenity for the entire community.

Chi-Rho Stone

This ancient standing stone is carved on two faces with the symbols ‘Chi’ and ‘Rho’, the first two letters of the name ‘Christ’ in Greek.

Chi-Rho stones are rare in Ireland and are more commonly seen in parts of Europe. To find this design carved in a local stone demonstrates that followers of the early church in this region had links with Christian communities overseas and knew Greek.

Another quality that makes this stone unique is that the Chi-Rho symbol on its opposite face has been reversed.

The stone is believed to have originally stood on a ridge in a nearby townland before being moved to its present site. It is known locally as ‘Old Patrick’. Local tradition states that it commemorates a visit by Saint Patrick, who inscribed the symbol on the stone with the tip of his finger.

The Chi-Rho Stone is on private land and cannot be accessed without the owner’s permission.

Megalithic Tombs

During the Neolithic Period (4,500-2,500BC), people began ritualising death and building large stone tombs. It is believed that the tombs were used to bury essential people from their communities, and approximately 1600 have been recorded in Ireland.

These tombs are remarkable for many reasons. Of particular interest are the vast stones (or megaliths) used to construct them. The megaliths were often carried a considerable distance to the site of the tomb. They were probably transported along rivers and then drawn to the site by rolling them over logs – it would be hundreds of years until the wheel would be used in Ireland.

Archaeological excavations have revealed a variety of artefacts at megalithic tombs. These have included axe heads, flint arrows, stone beads and pottery. It is thought that these artefacts were associated with death rituals. They may have been buried to help the deceased in the afterlife, or they may have reflected how important the individual was in the community. They may have been tokens chosen by the community to show their cultural or family bond with the individual.

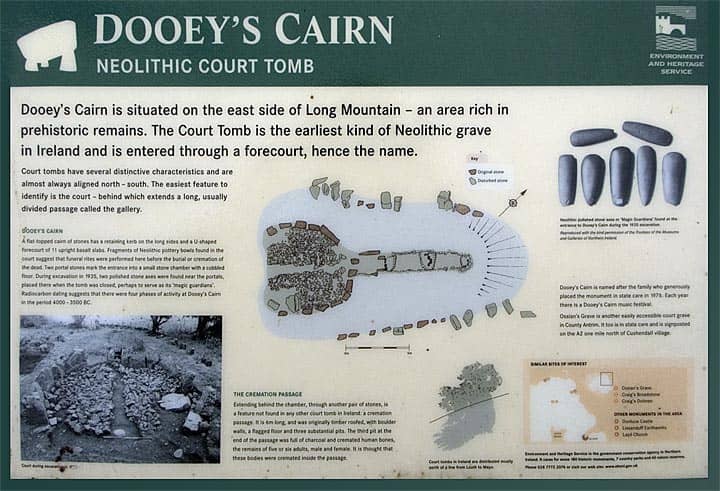

Dooeys Cairn

A Neolithic tomb dating from c.4000-2000 BC. This is the best-preserved court tomb in the Causeway Coast area. It is named after Andrew Dooey, who owned the land. His family granted it to the government in 1975.

It was excavated twice, in 1935 and 1975. It consists of a U-shaped forecourt that leads into a small chamber. Behind the chamber is a cremation passage containing three pits, one of which held the remains of five or six individuals. This form of cremation passage is the only one of its type found in Ireland.

During the excavations, archaeologists discovered various artefacts, e.g. polished axe heads, flint arrows and decorated pottery. Evidence of cereal seeds was also found, implying that early forms of agriculture had been introduced into this region at the time of the burials.

Dooey’s Cairn is maintained by the Northern Ireland Environment Agency and is accessible to the public.

The Broad Stone – Nr Long Mountain

The Broad Stone is a three-chambered court tomb with a shallow semi-circular forecourt. It is situated on the west side of Long Mountain, near Rasharkin. In the past, it was widely believed that precious artefacts had been buried in the tomb and treasure hunters disturbed much of the ground surrounding the megalithic stones. As a result, in 1883, the tomb collapsed, and locals had to rebuild it and reposition the capstone – the reconstructed tomb now resembles a ‘dolmen’ or portal tomb.

During penal times, Roman Catholics celebrated Mass here. The site was also popular for public gatherings, picnics and games.

The Northern Ireland Environment Agency maintains the Broad Stone. It is on private land and cannot be visited without the landowner’s permission

Craigs Dolmen

Craigs Dolmen has situated a short distance from the Broad Stone, on the eastern slopes of the Bann Valley. It is a passage tomb consisting of a single oval chamber formed by upright stones which support a capstone.

The tomb was previously almost covered with earth, with only the capstone exposed. A cinerary urn was discovered in the burial chamber when the soil was removed to expose the tomb.

By 1940, one of the upright stones had fallen. In 1985, this stone was restored, the tomb was reconstructed, and an archaeological excavation discovered cremated bone and more pottery.

The Northern Ireland Environment Agency maintains Craigs Dolmen. It is on private land and cannot be visited without the landowner’s permission

Ringforts

A ringfort is a circular enclosure surrounded by a raised earthen embankment and a ditch or moat. It is estimated that there are over 45,000 ringforts in Ireland, making them the most common ancient monument on the Island.

The majority were occupied between 600–900AD. The earliest ringforts date from the 5th century, while others were occupied until as late as the 13th century. Their function was to protect small settlements consisting of a family, workers, and livestock against raids. They would have been effective at repelling the lightning cattle raids that were common during the Early Christian period in Ireland (c.400-1200AD).

Several well-preserved examples of ringforts in the Ballymoney area include Benvarden, Moneycannon and Stranocum.

Excavations at Irish ringforts have uncovered a range of finds, including wheel-made pottery, glass beads, bronze & iron pins and bone, antler & metalwork.

Traditionally, ringforts were believed to be ritual sites or associated with supernatural forces, such as fairies or ‘wee folk’.

Castles

Motte and bailey castles were built by Anglo-Norman settlers in the period after they invaded Ulster in 1177. Many of them survive throughout the east of Ireland. While Earls lived in large stone castles, such as at Carrickfergus, their chief tenants, the Barons, lived in these smaller fortified dwellings.

The ‘motte’ was a large mound of earth with a flat platform on which a wooden tower was erected. A wooden palisade protected the forum. The ‘bailey’, or courtyard, was an embanked enclosure at the foot of the mound where most of the inhabitants would live.

The bailey would probably have contained buildings, e.g. a hall, large chamber, and barns. Few Irish mottes were built with a bailey, unlike those found in England or Europe. Those with baileys tend to be situated in regions where the inhabitants were at risk from attack and thought they may have had a military function.

In the Ballymoney area, examples of a typical motte can be found at Carrowcrin, near Loughguile, and Drumart, near Ballymoney. Knockahollet, also near Loughguile, is a well-preserved motte with a bailey.

Ballymoney Workhouse

The Irish Poor Law of 1838 introduced a relief system for poor, sick and needy people. Ireland was divided into 130 Poor Law Unions, with a workhouse established in each. The Ballymoney Workhouse was completed in 1843 and was managed by a Board of Guardians, elected by local rate-payers.

Families were separated and given a cold bath to de-louse them. Men, women and children were confined to their dormitories. During the day, they followed a strict regime and were expected to perform manual labour. Tasks included breaking stones, working in the laundry, digging trenches, picking oakum, cooking, and scrubbing floors. Their daily diet consisted of small quantities of oatmeal, soup, bread, potatoes and buttermilk.

The children were educated and taught a trade. Boys learned shoe making and tailoring, while girls were taught embroidery and cooking.

At the height of the famine in 1847, entire families were admitted to the Ballymoney Workhouse. At one point, it became vastly overcrowded with 870 inmates.

By the early 20th century, the number of people seeking relief had declined, and the workhouse closed in 1918. It later became the site of the Route Hospital.

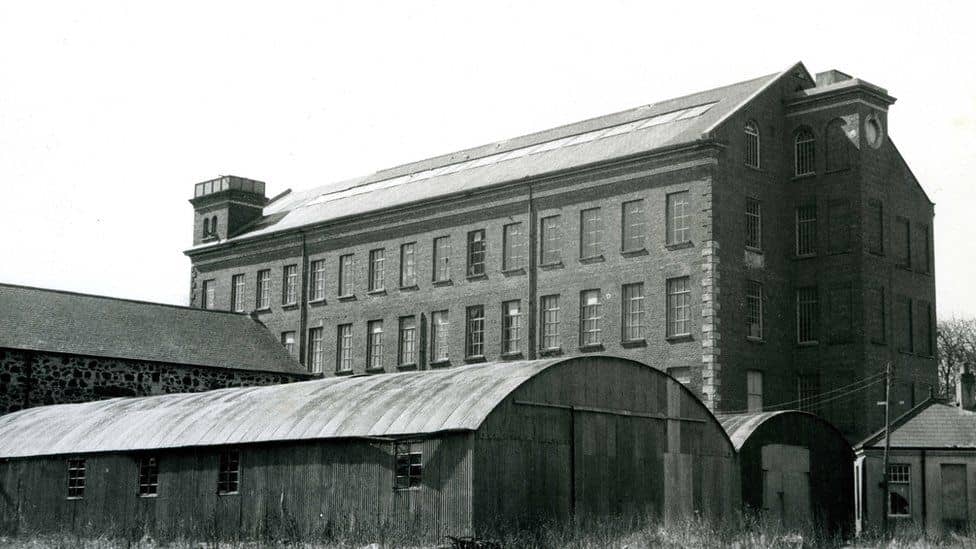

Balnamore Mill

In the early 19th Century, Balnamore was one of the largest spinning mills outside Belfast. In its prime, it employed more than 400 people. Despite the harsh conditions, locals who worked there recall it as an excellent place to work, with a strong sense of community.

In 1764, John Caldwell bought a corn mill and 40 acres of land at Harmony Hill, later named Balnamore. Caldwell added bleach works and a small beetling mill and soon ran a profitable business.

The mill later came under the control of Joseph Bryan. He installed 400 water-powered spindles and began making strong yarn for sail cloth and canvas.

A village began to develop around the mill, with houses for employees, a shop and a school. In later years, there was even a football team.

The mill was sold to Braidwater Spinning Company Ltd., of Ballymena, who extended it and introduced new water-powered turbines. In the 1920s, Braidwater Spinning Company Ltd sold it again to Hale, Martin & Co. Ltd.

In the 1930s, when the linen industry declined, the mill could not survive. The mill horn sounded for the last time on 27th February 1959.